I have wondered for quite a while now why "hope" has been taken away from the practice of medicine. I am getting older, and may retire in a year of two, but I see it in my younger colleagues. They look forward to working fewer hours, complaining about the ever increasing scrutiny of physicians, and the all too common government threats to reduce payments to physicians under Medicare. The milieu for practicing medicine is "not what it used to be."

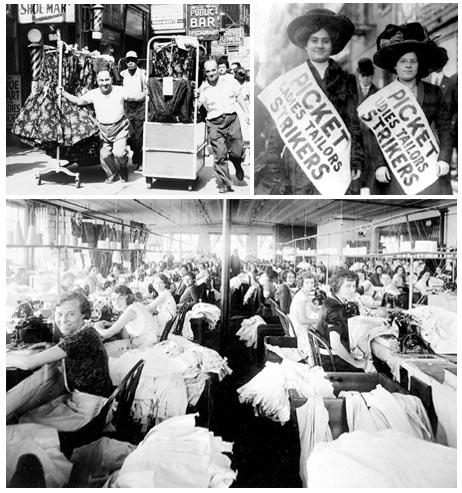

In reading a recent book, "Outliers:The Story of Success" by Malcolm Gladwell, I think I have found the answer. Mr. Gladwell tells the story of Mr. Borgenicht and his wife who started sewing aprons in their kitchen, and built a very successful business in the garment district of New York City. He describes in the following paragraph why Mr. Borgenicht was successful, and why he had "hope." Examining the field of medicine from the perspective that Mr. Gladwell examines the work of Mr. Borgenicht will help us expose the forces in medicine that taking hope out of our practices.

"When Borgenicht came home at night to his children, he may have been tired and poor and overwhelmed, but he was alive. He was his own boss. He was responsible for his own decisions and direction. His work was complex: it engaged his mind and imagination. And in his work, there was a relationship between effort and reward: the longer he and Regina (his wife) stayed up at night sewing aprons, the more money they made the next day on the streets... (my bold)Those three things-autonomy, complexity, and a connection between effort and reward-are, most people agree, the three qualities that work has to have if it is to be satisfying." Is practicing medicine satisfying these days? I would like to examine these three qualities in the practice of medicine: autonomy, complexity and connection between effort and reward.

How about autonomy. Physicians must pass Board Exams-I don't have a problem with that idea, but the exams are changing-every few years now, and they are now going to require continuous re-certification. I recently re-certified in cardio-thoracic surgery and the examination was effective, educational and enjoyable. I was treated like an adult, a professional. It was a take home exam which showed me a critique of the question after I tried to answer it the first time. After reviewing the critique (which contained the answer), I answered the question a second time. It was an educational process which I enjoyed even though I do not do most of the procedures I was queried about. Now, because of the increasing scrutiny of physicians, the exam will be a closed book exam that younger surgeons will have to travel to some hotel to take. Don't we have enough bureaucrats reviewing and checking on us at multiple levels? Ever hear of the "one hundred lives campaign?"

That's only one type of scrutiny. I haven't mentioned JACHO and its review on new doctors, and doctors private offices, and peer review, and CME requirements, and applications for privileges to hospitals, and even-if you can believe it- applying to be on an insurance company panel of "approved" doctors. If something bad happens in surgery, and it can happen, the review is never ending.

I once was placing a pacemaker in a very sick patient. She ended up doing alright, but during the case, she had a cardiac arrest. It was handled fine, and she survived without consequences. During her cardiac arrest,however, while I was resuscitating her, I actually thought, "I can't believe the bureaucracy I will have to go through if she dies!" What a confining and oppressive atmosphere in which to practice medicine. Autonomy is gone, and with it, any sense of professionalism that used to serve as the basis of a life of personal sacrifice for the patients. Are we going into medicine now as a "lifestyle" choice?

Mr. Gladwell's second requirement for hope in a vocation is complexity. I think all will agree that the physician's job is complex, but even the complexity is being threatened by intrusions of others into the daily work of the physician. Documentation has become so important in the field of medicine, that it is just about becoming medical care. At times, the patients seem to be getting in the way of this medical care, and if they would just go away, we could finish our documentation. Why so much documentation? It is done for legal and reimbursement reasons. It doesn't have anything to do with patient care.

In addition, we are told what to write. We can't say diabetes anymore, it has to be "type II diabetes," and anemia is now "blood loss anemia." Imagine controlling what a real professional must write, and how details must be written. Is that another limit on the ever disappearing reward of professional freedom?

Finally, their is a relationship "between effort and reward." There is none whatsoever. Third parties control this important aspect of any service relationship, and they have created systems that exist to decrease reimbursement to providers rather than fairly compensate the work of physicians. Most physicians don't know the details of the reimbursement, but they keep working harder, because they know that their income continues to drop while the bonuses of the third party administrators continues to increase.

I worry about medical care not so much because there are so many millions uninsured, and that most folks can't afford medical care, but I worry that the physicians and other "providers" are working in a field that does not satisfy Mr. Gladwell's requirements for a satisfying work environment. What does this portend for patients in the future? In a word, trouble. I think the relationship between the patient and the physician is dissolving. I think that in the future, there is a danger that when we are sick and vulnerable, and frightened, there will not be much of a connection with the person who is "in charge" of the decisions that will effect our life and limb. That does not bode well for our quest of "coverage for all."

James P. Weaver, M.D.,FACS